Authors

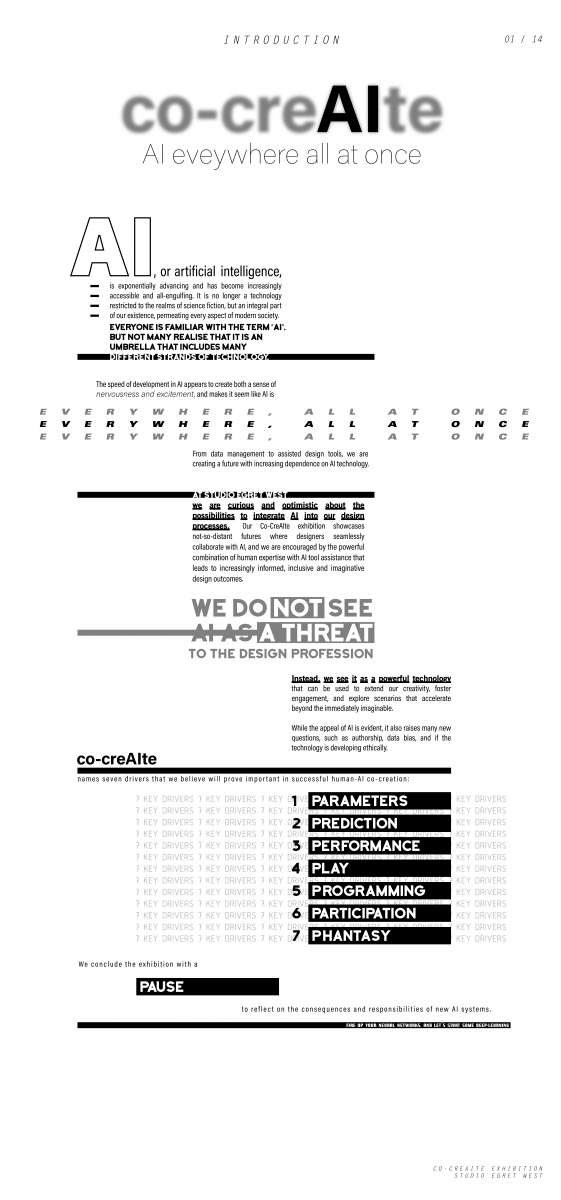

At Studio Egret West, we are curious and optimistic about the possibilities to integrate AI into our design processes. Our Co-CreAIte exhibition showcases not-so-distant futures where designers seamlessly collaborate with AI.

AI, or artificial intelligence, is exponentially advancing and has become increasingly accessible and all-engulfing. The speed of development in AI appears to create both a sense of nervousness and excitement, and makes it seem like AI is everywhere, all at once.

The technology is no longer restricted to the realms of science fiction, but now an integral part of our existence, permeating every aspect of modern society. Everyone is familiar with the term “AI”, but not many realise that it is an umbrella that includes many different strands of technology. From data management to assisted design tools, we are creating a future with increasing dependence on AI technology.

At Studio Egret West, we are encouraged by the powerful combination of human expertise with AI tool assistance that leads to increasingly informed, inclusive and imaginative design outcomes.

We do not see AI as a threat to the design profession. Instead, we see it as a powerful technology that can be used to extend our creativity, foster engagement, and explore scenarios that accelerate beyond the immediately imaginable. While the appeal of AI is evident, it also raises many new questions, such as authorship, data bias, and if the technology is developing ethically.

To gather our thoughts, Co-CreAIte names eight principles that we believe will prove important in successful human-AI co-creation: Parameters, Prediction, Performance, Play, Programming, Participation, Phantasy and Pause. These drivers will be crucial in understanding how design industries may evolve alongside emerging AI technology.

Want to know more? Fire up your neural networks, and let’s start some deep-learning!

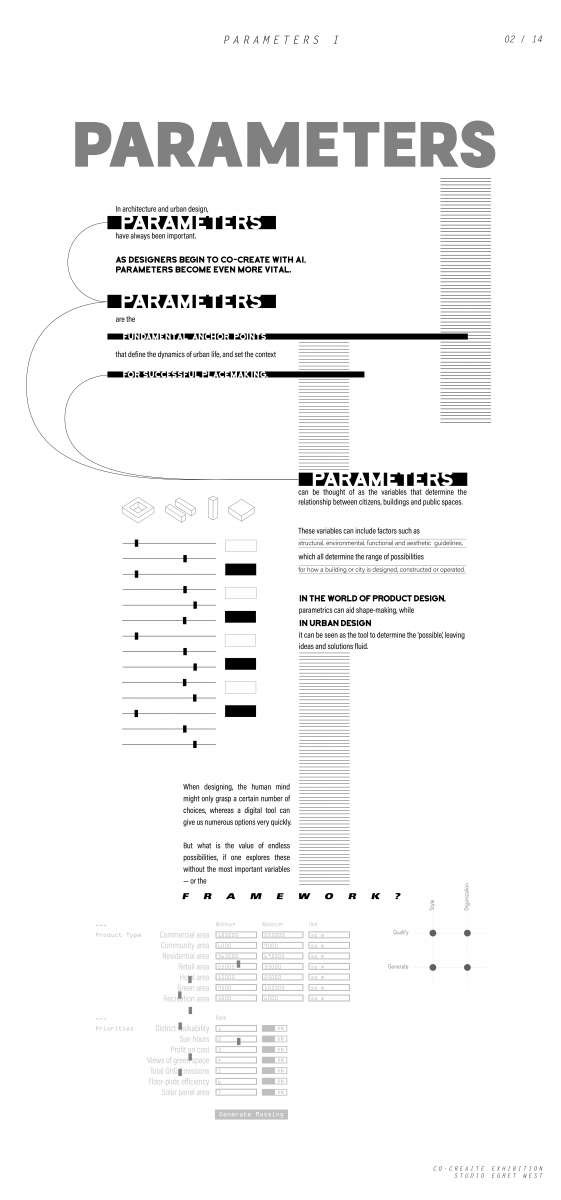

In architecture and urban design, parameters have always been important. As designers begin to co-create with AI, parameters become even more vital.

Parameters are the fundamental anchor points that define the dynamics of urban life, and set the context for successful placemaking. Parameters can be thought of as the variables that determine the relationship between citizens, buildings and public spaces. These variables can include factors such as structural, environmental, functional and aesthetic guidelines, which all determine the range of possibilities — how a building or city is designed, constructed or operated.

In the world of product design, parametrics can aid shape-making, while in urban design it can be seen as the tool to determine the ‘possible’, leaving ideas and solutions fluid.

When designing, the human mind might only grasp a certain number of choices, whereas a digital tool can give us numerous options very quickly. But what is the value of endless possibilities, if one explores these without the most important variables — or the framework?

Parameters set the framework within which humans and AI can co-create. As designers, we can utilise and alter these parameters with rigour, to guide the algorithms to generate a desired output. The resultant designer is not a ‘generator’ of different options, but someone that sets the parameters that carry value and defines the framework that decerns between infinite possibilities. Human expertise then reflects and distils options using values, judgement and sensitivity.

This suggests a potential shift in the role that designers play, if AI becomes more heavily integrated into design workflows.

Agreeing with this is Daniel Bolojan, one of the leading voices in implementing deep-learning AI strategies into architectural design processes. He states that “The role of creativity in the design process is in defining the constraints that generate a range of possibilities. It's no longer a question of defining the ideal design, but rather of reviewing the entire design space of possible sample outcomes, selecting and enhancing the best solution.”

Seems like it all starts, ends, and starts again – with parameters.

Did you know?

Long before the invention of computer-aided design, Antonio Gaudi effectively experimented with an analog “parametric” design process by hanging string models of his buildings upside-down, then, using mirrors on the floor, visualising his designs downside-up. 5 One touted feature of modern parametric design software is the ability to update a model any time its parameters are altered, allowing alternatives to be quickly studied and compared. Gaudí’s hanging chains do exactly that: if a chain endpoint is moved, the shape of the entire hanging chain model shifts and settles into a newly optimised geometry. Of course, today’s parametric design softwares do a great deal more, but at their conceptual root, both of these modelling tools use procedural techniques to generate resulting forms.

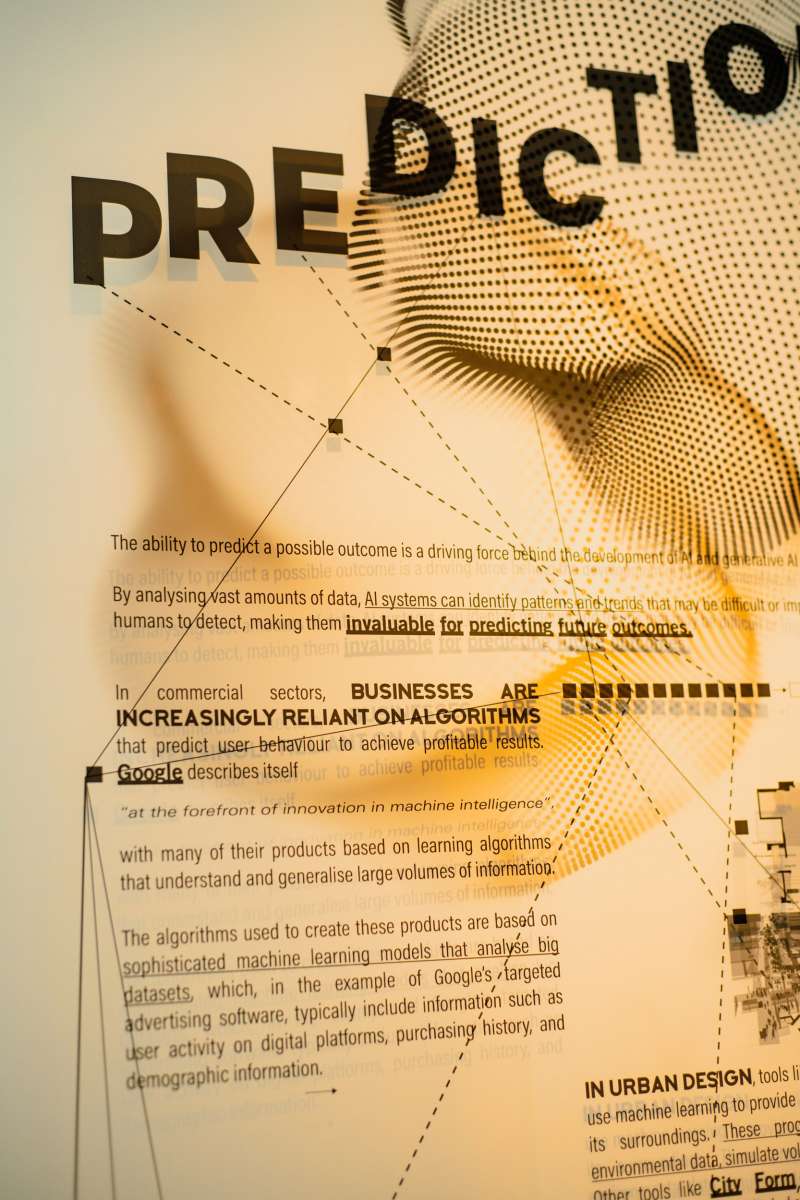

The ability to predict a possible outcome is a driving force behind the development of AI and generative AI systems. By analysing vast amounts of data, AI systems can identify patterns and trends that may be difficult or impossible for humans to detect, making them invaluable for predicting future outcomes.

In commercial sectors, businesses are increasingly reliant on algorithms that predict user behaviour to achieve profitable results. Google describes itself “at the forefront of innovation in machine intelligence”, with many of their products based on learning algorithms that understand and generalise large volumes of information. The algorithms used to create these products are based on sophisticated machine learning models that analyse big datasets, which, in the example of Google’s targeted advertising software, typically include information such as user activity on digital platforms, purchasing history, and demographic information.

In urban design, tools like Spacemaker or Delve use machine learning to provide greater insight into a site and its surroundings. These programmes analyse extensive environmental data, simulate volumes and optimise site usage. Other tools like City Form Lab or MassMotion use algorithms to predict crowded spaces and identify busy streets and safe cycle routes, among other aspects of urban environments. By simulating these scenarios, these tools can help urban planners and architects to design cities that are safer and more efficient.

Jan Bunge from SquintOpera has suggested that we take this idea further, by building a “digital twin” of planet Earth. In this way, designers and communities would have a sandbox in which to simulate their designs in, with access to all relevant, cross-disciplinary data. This would create a revolutionary new way to design, enabling designers to optimise, reiterate and learn in a fully-simulated environment.

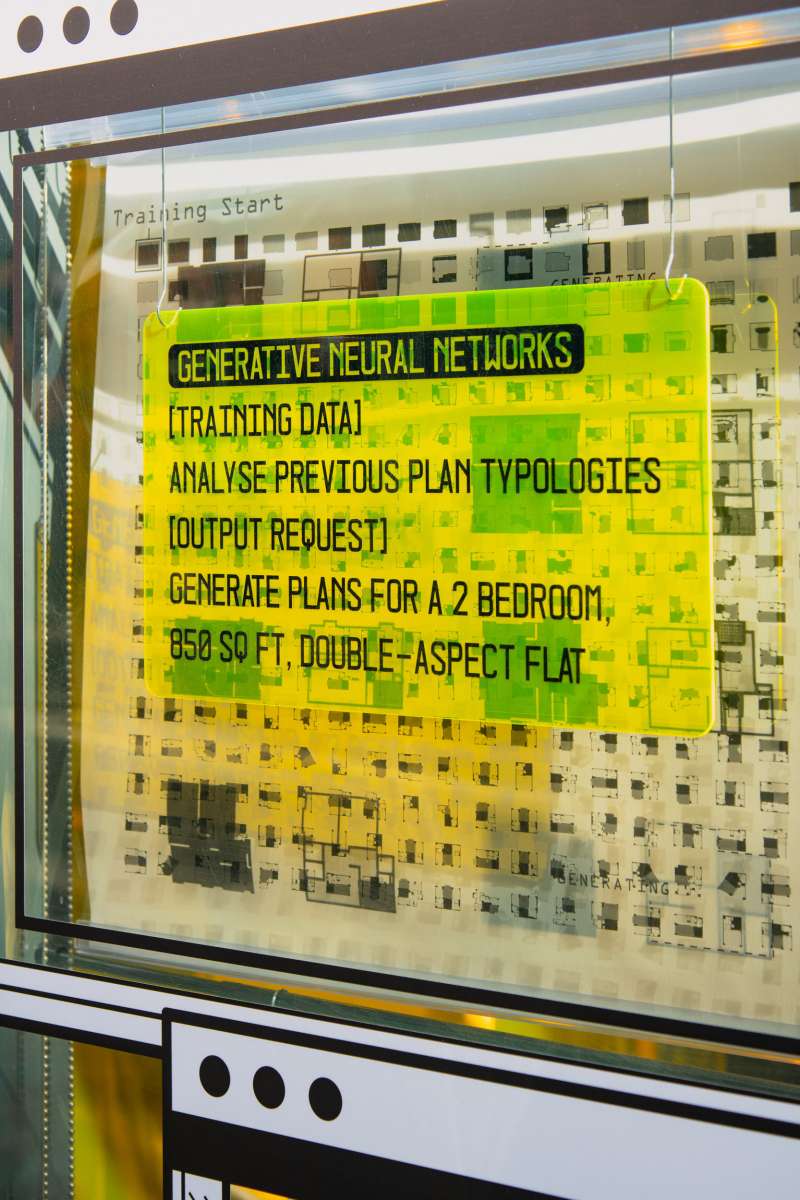

In the architectural and building scale, simulations are often employed during the optioneering stages of designs. Products like PlanFinder generate floor plans in given boundaries, while adjusting them to local regulations and specified factors.

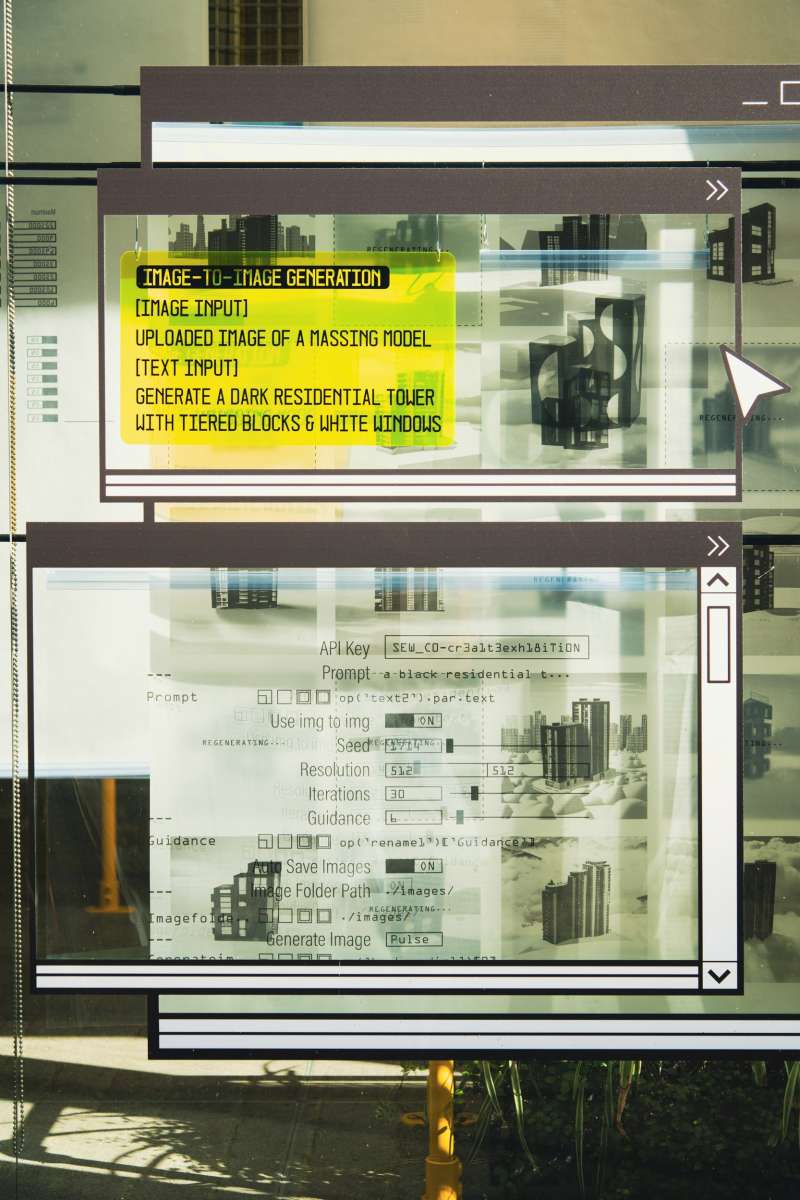

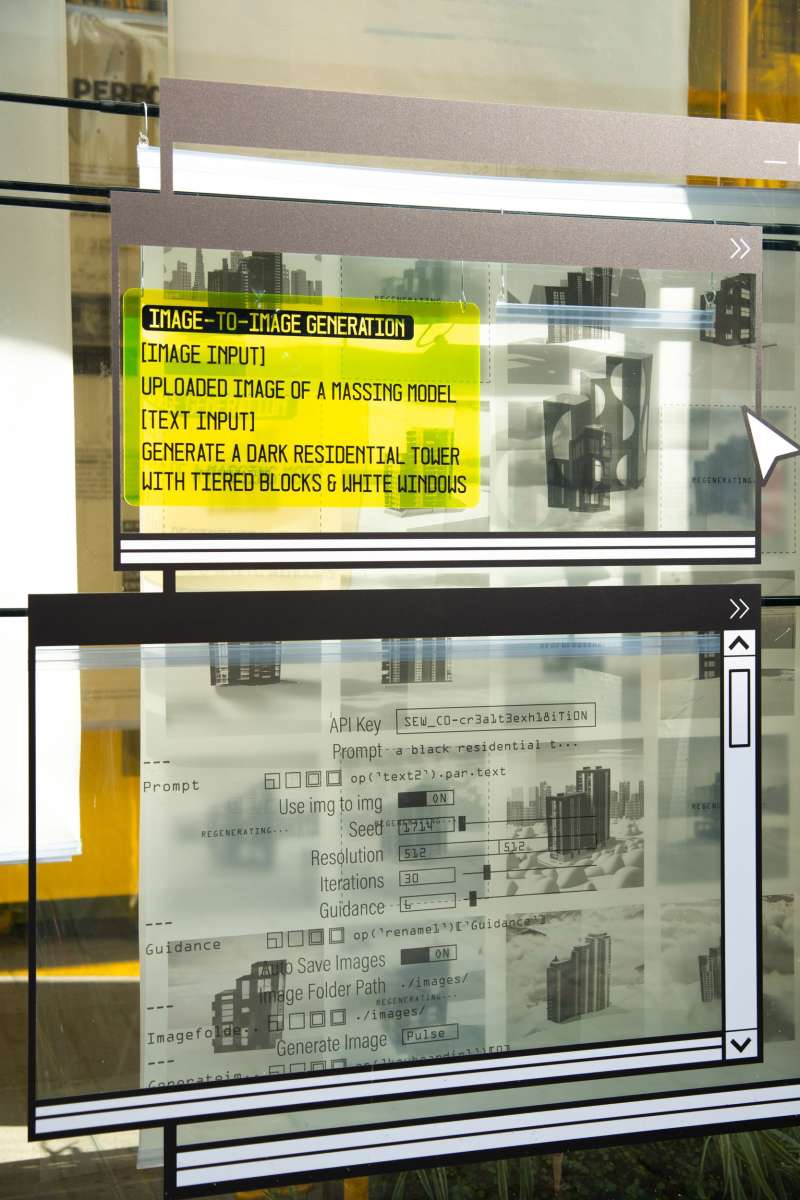

AI does not only power data-analysis, but also has been integrated into other types of software that focus on visual simulations. With vision being a dominant sense in architecture, having more powerful visual tools to digitally simulate spaces has become highly sought after.

Today, digital rendering programmes enable convincing virtual representation, with AI improving visual accuracy, increasing speed of production, and assisting creation. New tools are constantly being developed to improve these experiences. For example, NVIDIA recently presented Instant NeRF, a neural rendering model that quickly turns 2D photos into accurate 3D models, creating new ways to model spaces digitally.

In time, AI technologies will pave the way for a seamless future with real-time visual communication, integrated data showcasing, and enhanced virtual spatial experiences. This will allow designers to visualise spaces in virtual or hybrid worlds, opening the door for simulated predictions of experiences, sensations and triggers even in the concept stages of their projects.

Studio Egret West: AI Exhibition Opening Night

Studio Egret West: AI Exhibition Opening Night

With urbanisation at an all-time high, cities around the world are facing unprecedented challenges to manage their environments and resources sustainably, and many employ management tools to measure and improve environmental performance. Though AI seems like a recent trend in popular culture, AI-assisted data management for urban and building scales have already been at work for over two decades.

Behind the scenes, these tools allow access to crucial empirical data to both monitor environments and alter them with accountability. From traffic control to waste management, data analytics are designed to provide patterns, predictions and automated guidance.

One of the earliest examples of this is City Brain, developed by the Alibaba Group. This technology was adopted by local governments in China and was designed as an AI-assisted traffic management tool, using data from the transportation bureau, public transportation systems, a mapping app and hundreds of thousands of cameras. When the system was initially given control of 104 traffic light junctions in Hangzhou’s Xiaoshan district, resultant traffic speed increased by 15% in the first year of operation. The system was soon rolled out to the rest of the city, with Alibaba later expanding the technology to 22 other cities. [1]

On the other side of the globe, the Copenhagen Connecting system was similarly launched, and has measurably improved quality of life. The system utilizes wireless data from mobile phones, GPS devices on buses, and sensors in sewers and garbage cans to help reduce congestion, air pollution, and carbon dioxide emissions. This smart city project won the 2014 award for the best smart city project in the world, and once fully implemented, it is expected to result in a socio-economic gain of €600 million. [2]

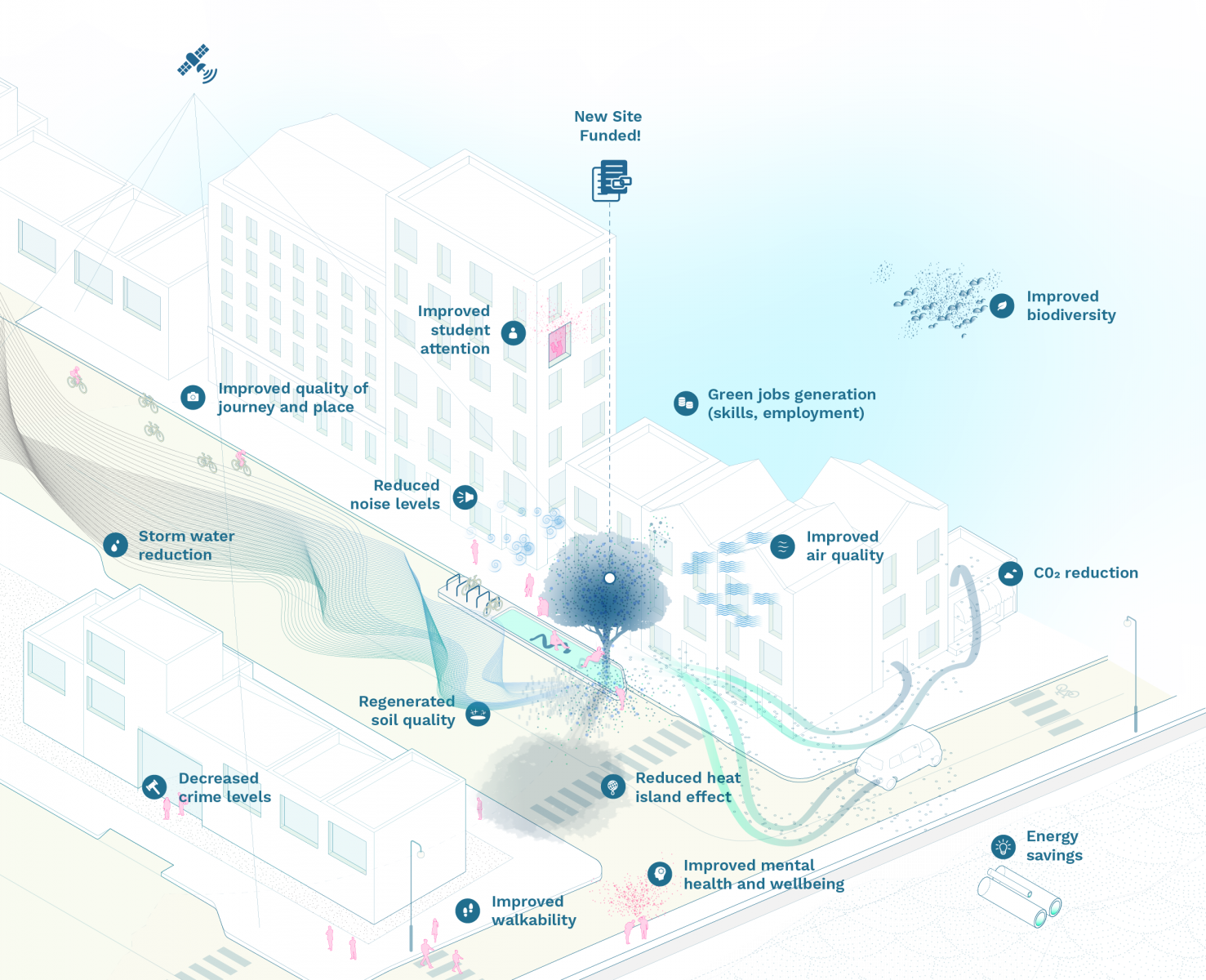

As another example of performative AI technology, TreesAI is a platform developed by Dark Matter Labs and Lucidminds that manages the performance of nature-based solutions in urban planning. By correlating this data with economic, health, and environmental factors, TreesAI provides planners with a comprehensive overview of the natural assets within a given site, and utilising iterative algorithms, enables them to make informed decisions about designing and managing green spaces.

AI has the potential to revolutionise the way we monitor and assess the performance of our built environment. Whether it is post-occupancy monitoring of a building, or real-time assessments of infrastructure, AI can help unlock the performance of existing or new assets, resulting in improved outcomes for building occupants and infrastructure users alike.

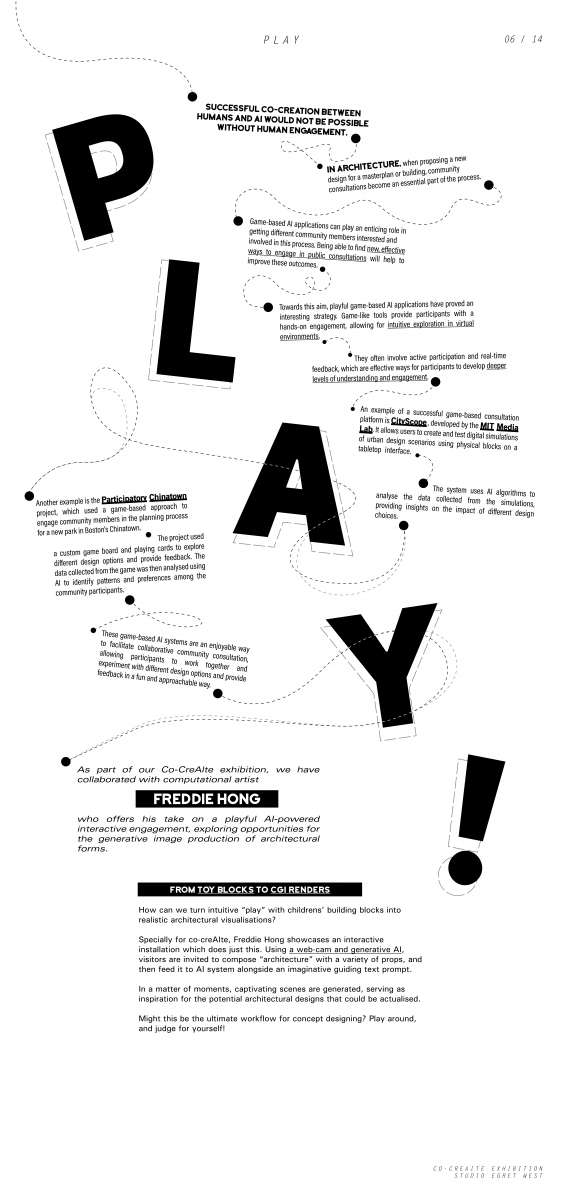

Successful co-creation between humans and AI would not be possible without human engagement. In architecture, when proposing a new design for a masterplan or building, community consultations become an essential part of the process. Game-based AI applications can play an enticing role in getting different community members interested and involved in this process. Being able to find new, effective ways to engage in public consultations will help to improve these outcomes.

Towards this aim, playful game-based AI applications have proved an interesting strategy. Game-like tools provide participants with a hands-on engagement, allowing for intuitive exploration in virtual environments. They often involve active participation and real-time feedback, which are effective ways for participants to develop deeper levels of understanding and engagement.

An example of a successful game-based consultation platform is ‘CityScope’, developed by the MIT Media Lab. It allows users to create and test digital simulations of urban design scenarios using physical blocks on a tabletop interface. The system uses AI algorithms to analyse the data collected from the simulations, providing insights on the impact of different design choices.

Another example is the ‘Participatory Chinatown’ project, which used a game-based approach to engage community members in the planning process for a new park in Boston’s Chinatown. The project used a custom game board and playing cards to explore different design options and provide feedback. The data collected from the game was then analysed using AI to identify patterns and preferences among the community participants.

These game-based AI systems are an enjoyable way to facilitate collaborative community consultation, allowing participants to work together and experiment with different design options and provide feedback in a fun and approachable way.

As part of our Co-CreAIte exhibition, we have collaborated with computational artist Freddie Hong, who offers his take on a playful AI-powered interactive engagement, exploring opportunities for the generative image production of architectural forms.

"PLAY!" by Freddie Hong

SEW commissioned computational artist Freddie Hong to create an installation that would introduce the concept of generative AI to visitors in a fun and intuitive way.

PLAY! is an interactive programme that features a combination of image-to-image and text-to-image generative processes. With a variety of wooden blocks, figurines and coloured mats, participants are invited to compose a scene that feeds through to a live webcam. They then provide a guiding text prompt which very quickly transforms the scene into any imaginable image.

The playful nature of the creation process is engaging, and participants can easily imagine how such a tool could easily integrate into the workflow of creative design work. For example, quick sketch models could be crafted out of paper and card, fed to the programme, and transformed into imaginative visualisations to quickly communicate design ideas.

To see more of Freddie's work, visit Instagram @freddie_hong_ or https://freddiehong.com/

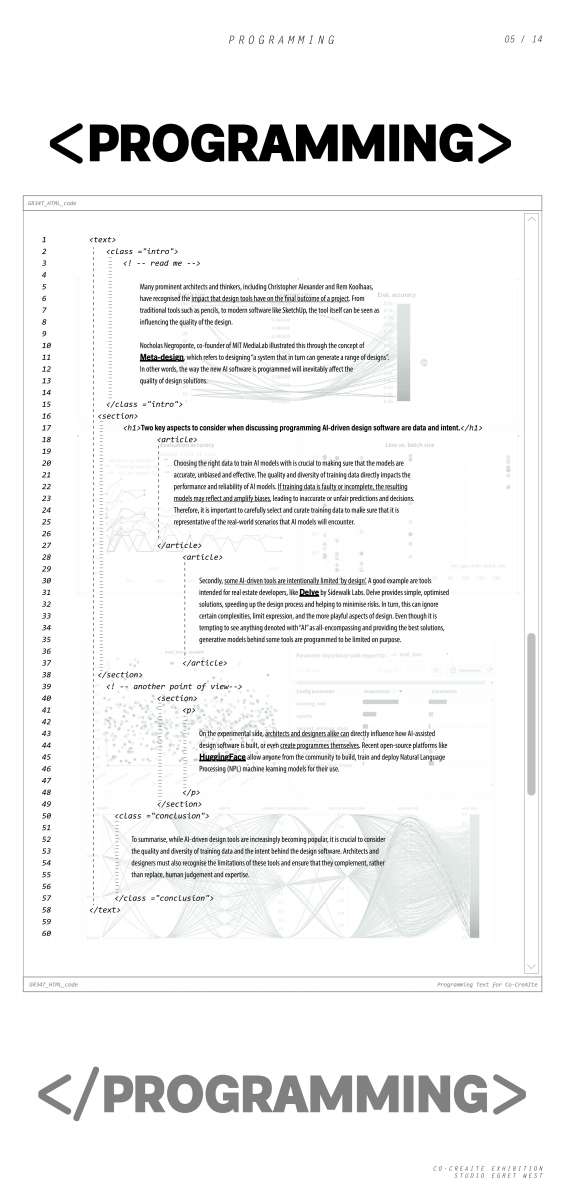

Many prominent architects and thinkers, including Christopher Alexander and Rem Koolhaas, have recognised the impact that design tools have on the final outcome of a project. From traditional tools such as pencils, to modern software like SketchUp, the tool itself can be seen as influencing the quality of the design.

Nocholas Negroponte, co-founder of MIT MediaLab illustrated this through the concept of Meta-design, which refers to designing “a system that in turn can generate a range of designs”. In other words, the way the new AI software is programmed will inevitably affect the quality of design solutions.

Two key aspects to consider when discussing programming AI-driven design software are data and intent.

Choosing the right data to train AI models with is crucial to making sure that the models are accurate, unbiased and effective. The quality and diversity of training data directly impacts the performance and reliability of AI models. If training data is faulty or incomplete, the resulting models may reflect and amplify biases, leading to inaccurate or unfair predictions and decisions. Therefore, it is important to carefully select and curate training data to make sure that it is representative of the real-world scenarios that AI models will encounter.

Secondly, some AI-driven tools are intentionally limited ‘by design’. A good example are tools intended for real estate developers, like Delve by Sidewalk Labs. Delve provides simple, optimised solutions, speeding up the design process and helping to minimise risks. In turn, this can ignore certain complexities, limit expression, and the more playful aspects of design. Even though it is tempting to see anything denoted with “AI” as all-encompassing and providing the best solutions, generative models behind some tools are programmed to be limited on purpose.

On the experimental side, architects and designers alike can directly influence how AI- assisted design software is built, or even create programmes themselves. Recent open-source platforms like HuggingFace allow anyone from the community to build, train and deploy Natural Language Processing (NPL) machine learning models for their use.

To summarise, while AI-driven design tools are increasingly becoming popular, it is crucial to consider the quality and diversity of training data and the intent behind the design software. Architects and designers must also recognise the limitations of these tools and ensure that they complement, rather than replace, human judgement and expertise.

Studio Egret West: AI Exhibition Opening Night

Studio Egret West: AI Exhibition Opening Night

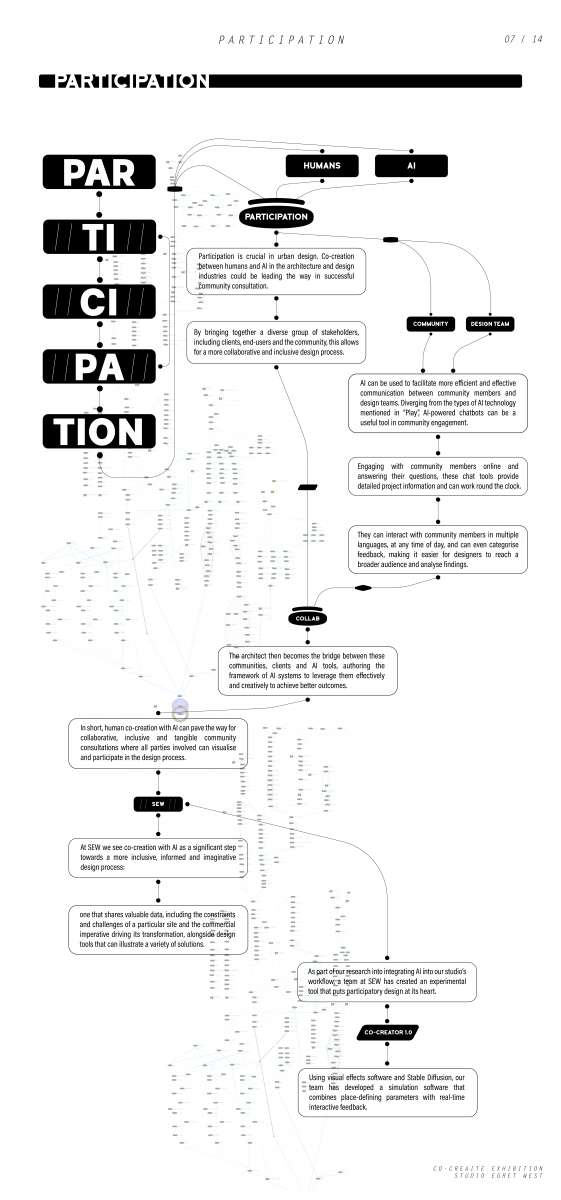

Participation is crucial in urban design. Co-creation between humans and AI in the architecture and design industries could be leading the way in successful community consultation. By bringing together a diverse group of stakeholders, including clients, end-users and the community, this allows for a more collaborative and inclusive design process.

AI can be used to facilitate more efficient and effective communication between community members and design teams. Diverging from the types of AI technology mentioned in “Play”, AI-powered chatbots can be a useful tool in community engagement. Engaging with community members online and answering their questions, these chat tools provide detailed project information and can work round the clock. They can interact with community members in multiple languages, at any time of day, and can even categorise feedback, making it easier for designers to reach a broader audience and analyse findings.

The architect then becomes the bridge between these communities, clients and AI tools, authoring the framework of AI systems to leverage them effectively and creatively to achieve better outcomes.

In short, human co-creation with AI can pave the way for collaborative, inclusive and tangible community consultations where all parties involved can visualise and participate in the design process. At SEW we see co-creation with AI as a significant step towards a more inclusive, informed and imaginative design process: one that shares valuable data, including the constraints and challenges of a particular site and the commercial imperative driving its transformation, alongside design tools that can illustrate a variety of solutions.

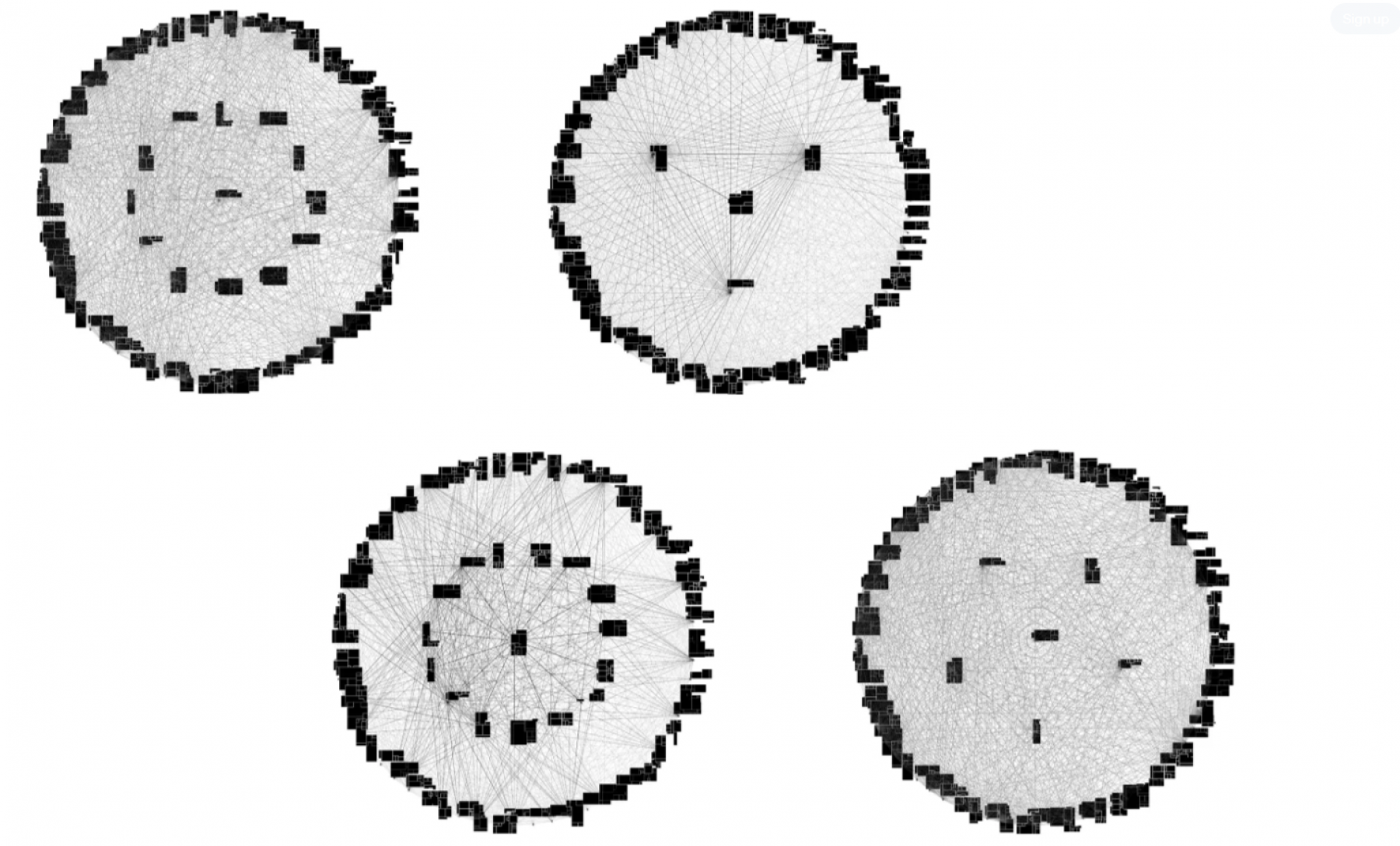

As part of our research into integrating AI into our studio’s workflow, a team at SEW has created an experimental tool that puts participatory design at its heart. Using visual effects software and Stable Diffusion, our team has developed a simulation software that combines place-defining parameters with real-time interactive feedback.

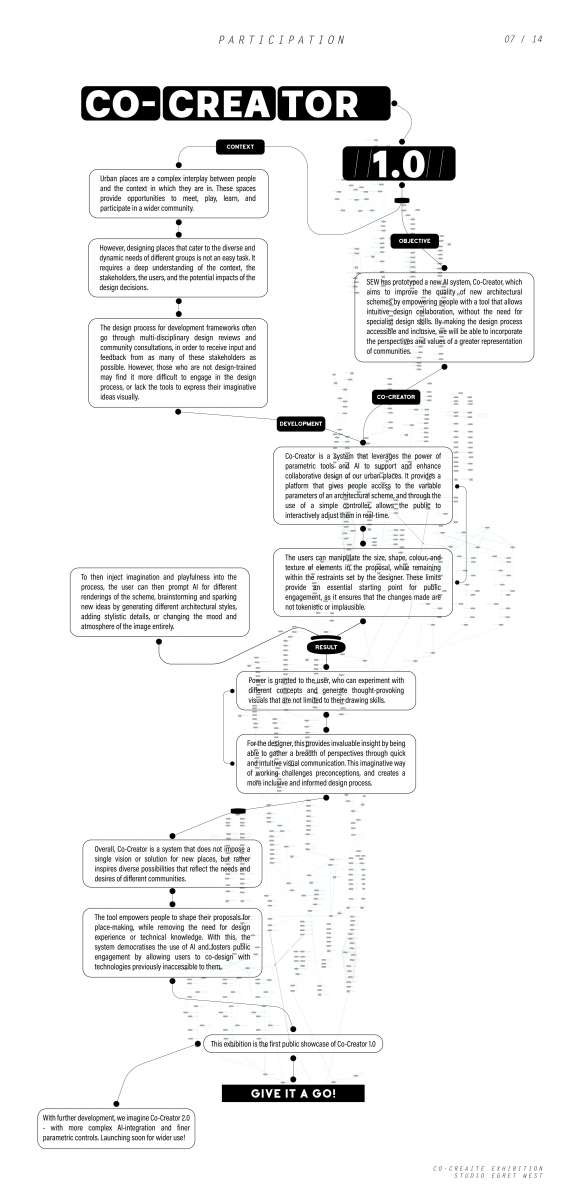

Co-Creator 1.0

SEW has prototyped a new AI system, Co-Creator, which aims to improve the quality of new architectural schemes by empowering people with a tool that allows intuitive design collaboration, without the need for specialist design skills. The design process for development frameworks often go through multi-disciplinary design reviews and community consultations, in order to receive input and feedback from as many of these stakeholders as possible. However, those who are not design-trained may find it more difficult to engage in the design process, or lack the tools to express their imaginative ideas visually. By making the design process accessible and inclusive, we will be able to incorporate the perspectives and values of a greater representation of communities.

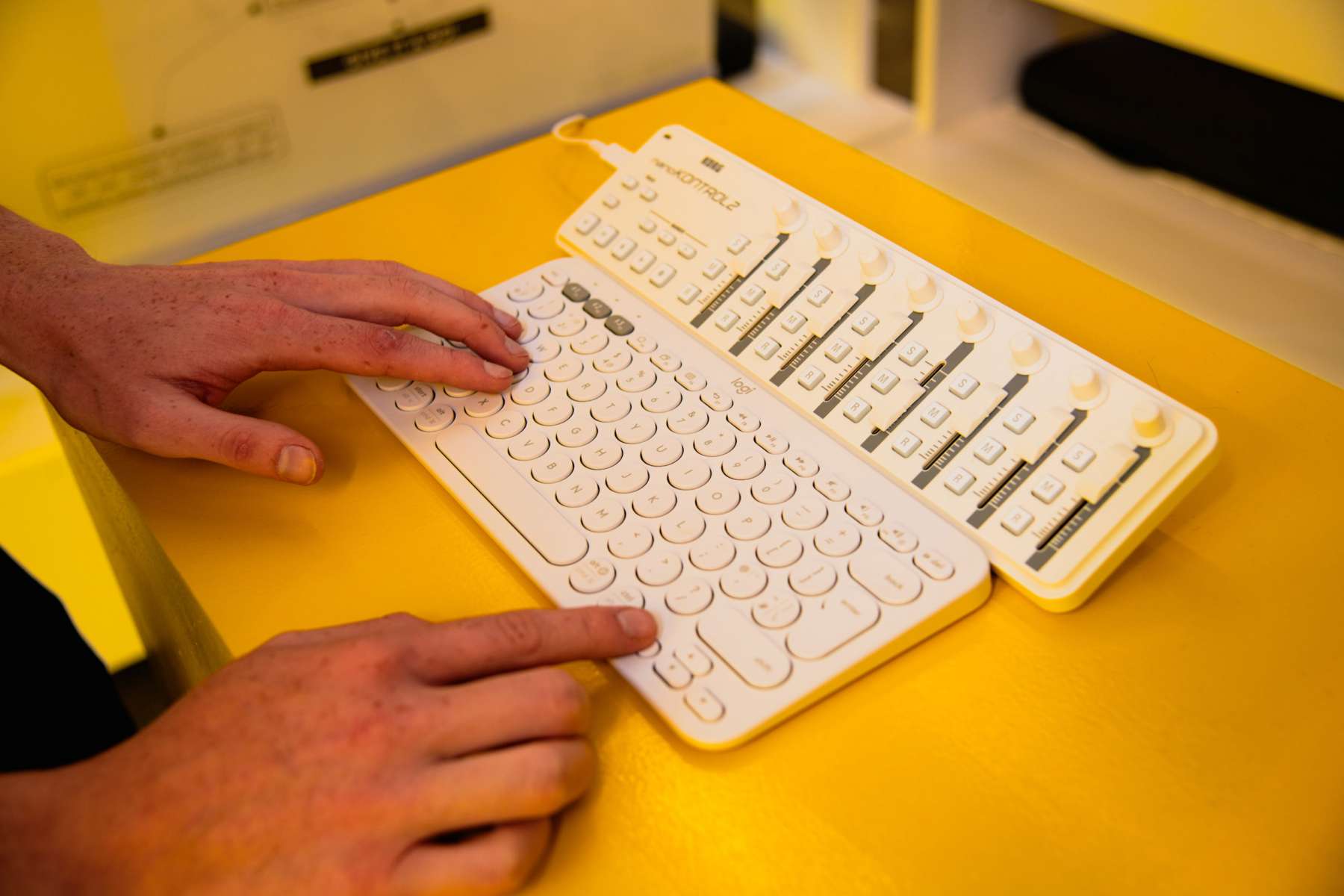

Co-Creator is a system that leverages the power of parametric tools and AI to support and enhance collaborative design of our urban places. It provides a platform that gives people access to the variable parameters of an architectural scheme, and through the use of a simple controller, allows the public to interactively adjust them in real-time. Users can manipulate the size, shape, colour, and texture of elements in the proposal, while remaining within the restraints set by the designer. These limits provide an essential starting point for public engagement, as it ensures that the changes made are not tokenistic or implausible.

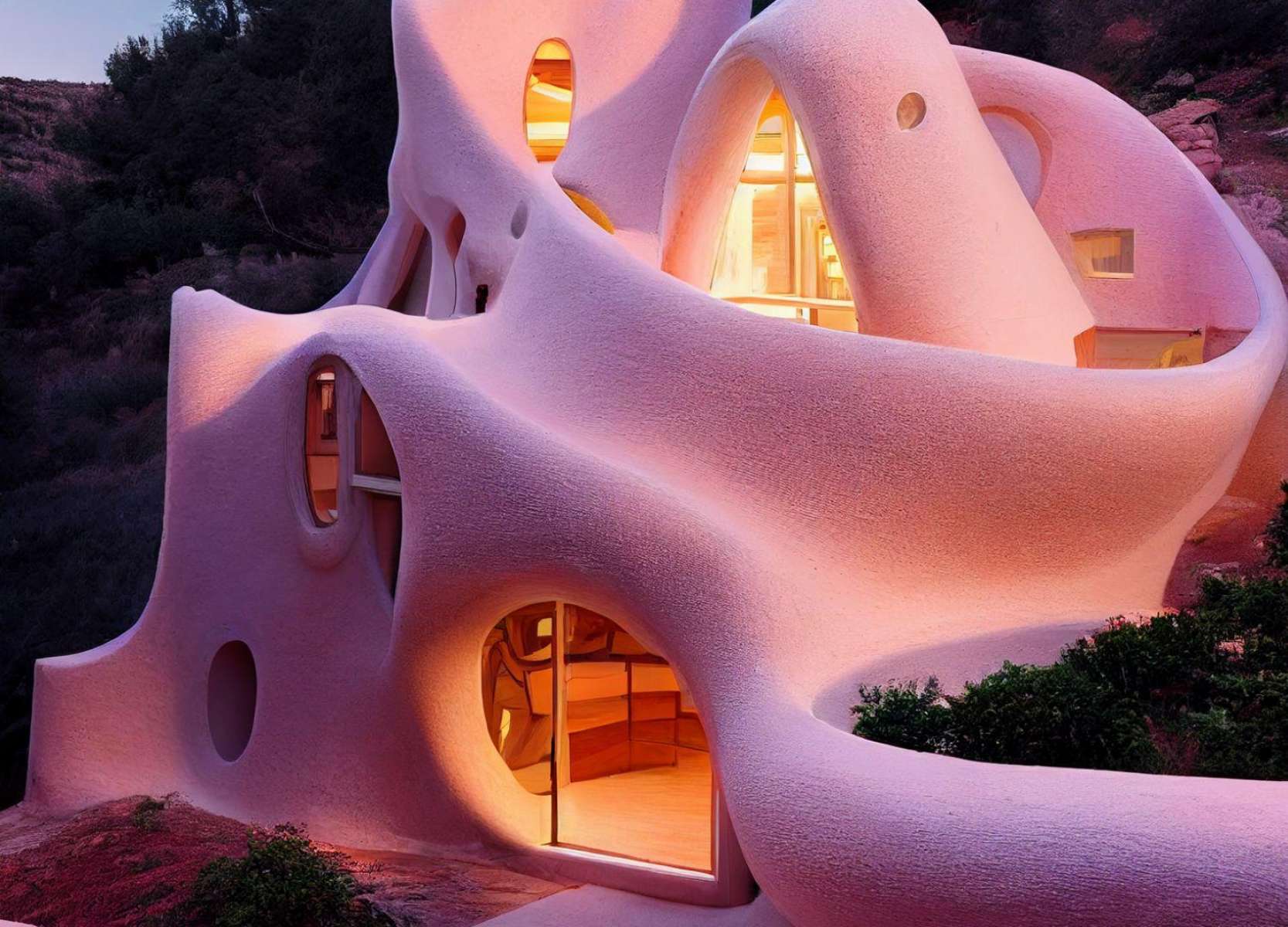

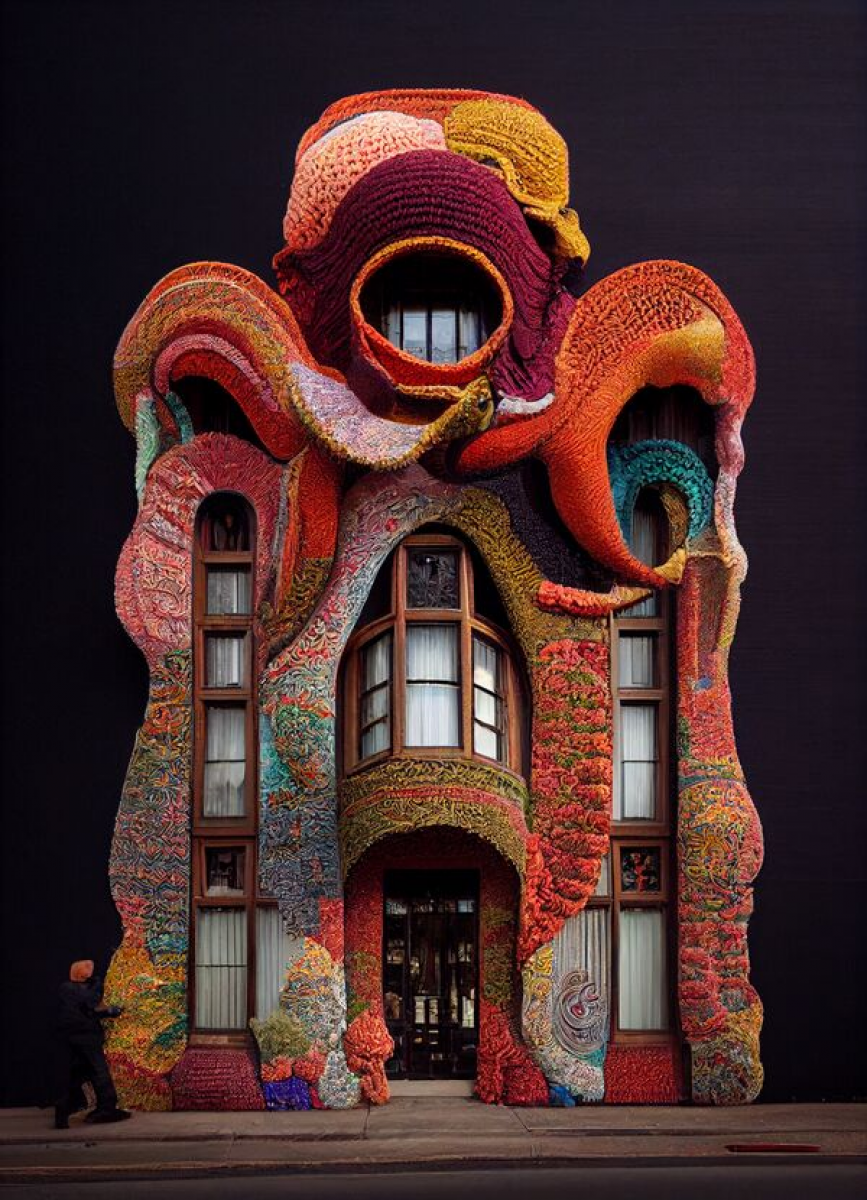

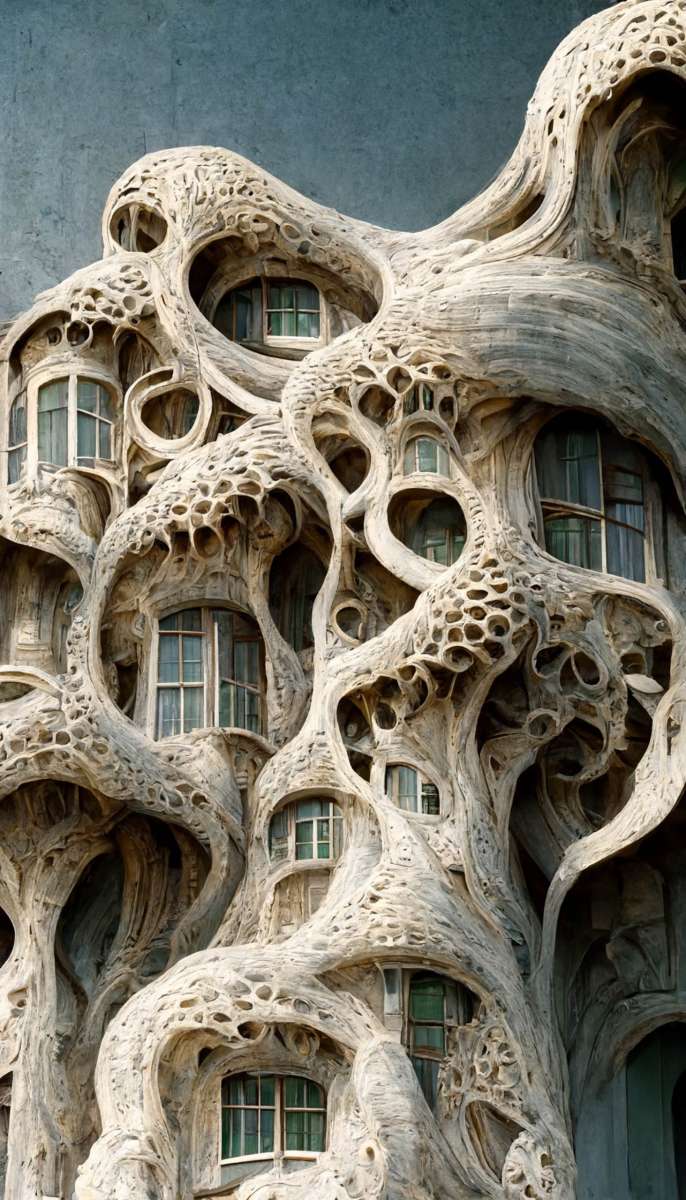

To then inject imagination and playfulness into the process, the user can then prompt AI for different renderings of the scheme, brainstorming and sparking new ideas by generating different architectural styles, adding stylistic details, or changing the mood and atmosphere of the image entirely. Power is granted to the user, who can experiment with different concepts and generate thought-provoking visuals that are not limited to their drawing skills.

For the designer, this provides invaluable insight by being able to gather a breadth of perspectives through quick and intuitive visual communication. This imaginative way of working challenges preconceptions, and creates a more inclusive and informed design process.

Overall, Co-Creator is a system that does not impose a single vision or solution for new places, but rather inspires diverse possibilities that reflect the needs and desires of different communities. The tool empowers people to shape their proposals for place-making, while removing the need for design experience or technical knowledge. With this, the system democratises the use of AI and fosters public engagement by allowing users to co-design with technologies previously inaccessible to them.

This exhibition is the first public showcase of Co-Creator 1.0, and its development was led by SEW's in-house digital specialist Bodhi Horton.

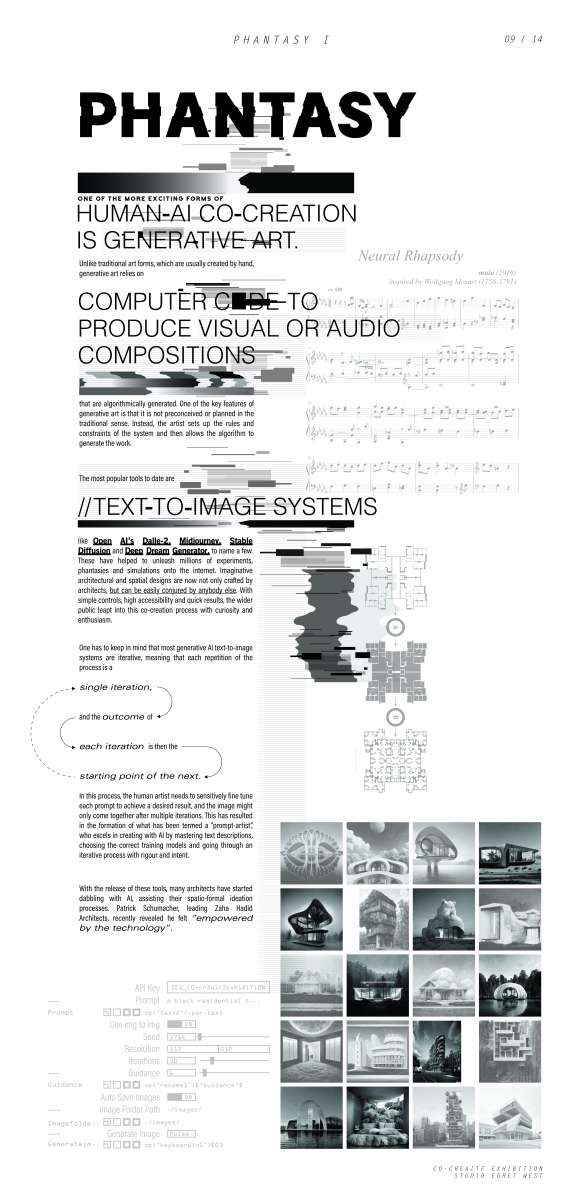

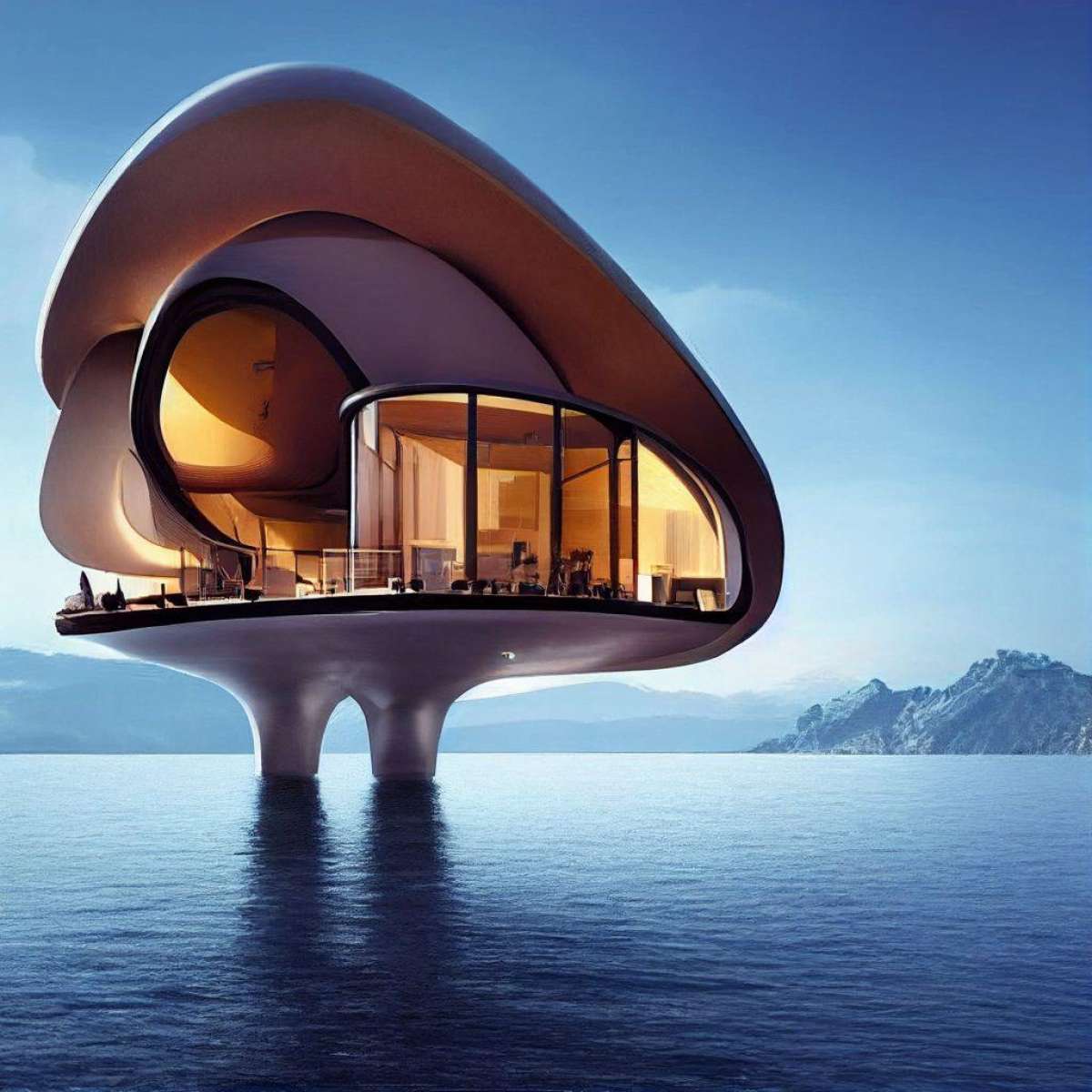

One of the more exciting forms of human-AI co-creation is in generative art. Unlike traditional art forms, which are usually created by hand, generative art relies on computer code to produce visual or audio compositions that are algorithmically generated. One of the key features of generative art is that it is not preconceived or planned in the traditional sense. Instead, the artist sets up the rules and constraints of the system and then allows the algorithm to generate the work.

The most popular tools to date are text-to-image systems, like Open AI’s Dalle-2, Midjourney, Stable Diffusion and Deep Dream Generator, to name a few. These have helped to unleash millions of experiments, phantasies and simulations onto the internet. Imaginative architectural and spatial designs are now not only crafted by architects, but can be easily conjured by anybody else. With simple controls, high accessibility and quick results, the wider public leapt into this co-creation process with curiosity and enthusiasm.

One has to keep in mind that most generative AI text-to-image systems are iterative, meaning that each repetition of the process is a single iteration, and the outcome of each iteration is then the starting point of the next. In this process, the human artist needs to sensitively fine tune each prompt to achieve a desired result, and the image might only come together after multiple iterations. This has resulted in the formation of what has been termed a “prompt-artist”, who excels in creating with AI by mastering text descriptions, choosing the correct training models and going through an iterative process with rigour and intent.

With the release of these tools, many architects have started dabbling with AI, assisting their spatio-formal ideation processes. Patrick Schumacher, leading Zaha Hadid Architects, recently revealed he felt “empowered by the technology”.

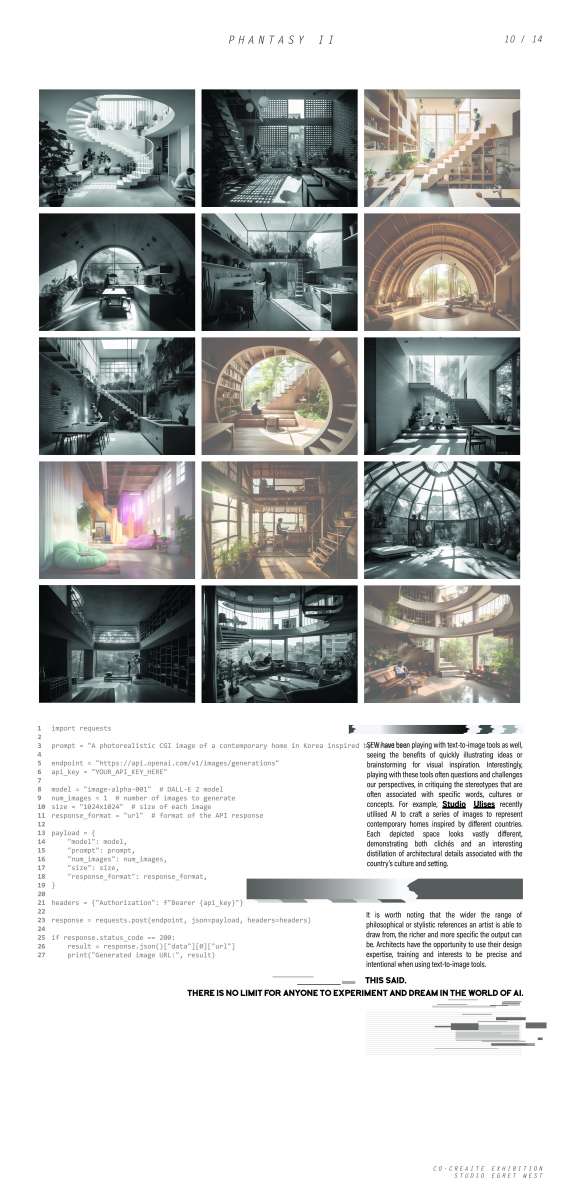

SEW have been playing with text-to-image tools as well, seeing the benefits of quickly illustrating ideas or brainstorming for visual inspiration. Interestingly, playing with these tools often questions and challenges our perspectives, in critiquing the stereotypes that are often associated with specific words, cultures or concepts. For example, Studio Ulises recently utilised AI to craft a series of images to represent contemporary homes inspired by different countries. Each depicted space looks vastly different, demonstrating both clichés and an interesting distillation of architectural details associated with the country’s culture and setting.

It is worth noting that the wider the range of philosophical or stylistic references an artist is able to draw from, the richer and more specific the output can be. Architects have the opportunity to use their design expertise, training and interests to be precise and intentional when using text-to-image tools. This said, there is no limit for anyone to experiment and dream in the world of AI.

The speed of advancement in AI technology can be both exciting and overwhelming at the same time. Therefore, it is important to pause and reflect on the consequences and responsibilities of new AI systems. It is too easy to get pulled along by the rush of rapid progress, that we side-line the social obligations that should be faced with developing and implementing advanced AI tools.

So, what does the future of AI spell for mankind?

Perhaps not surprisingly, casual conversations often joke that AI will lead to doomsday for humanity. But perhaps this fear is not unfounded.

It is remarkable that many of the individuals who are dedicated to the advancement of artificial intelligence are also concerned about the potential negative consequences it may have for humanity. Even those at the forefront of AI research acknowledge that their work could potentially lead to the destruction of the human race, or at the very least, significant harm. According to a 2022 survey, half of leading AI researchers agreed that there is a minimum of ten-percent likelihood that AI will cause “extremely bad outcomes” to the human race. [3] In the same vein, almost 70% of the respondents agreed that society should prioritise AI safety research more than is currently done. Even Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, has expressed comparable concerns.

A lot of this fear stems from the mysteriousness of AI, and the idea that its pseudo-sentient “intelligence” will one day escape mankind’s ability to understand and control. But should we be thinking this way?

Computer scientist and philosophy writer Jaron Lanier doesn’t think so, believing that “the most pragmatic position is to think of AI as a tool, not a creature.” [4] According to Lanier, portraying AI as a mystical entity only increases the likelihood of misunderstandings and failing to imaginatively employ the technology to its full potential. Such a mindset constrains our creativity, tying us to outdated visions of what AI can do. Instead, we should work with the mentality that AI is not some magical force but a man-made technology. The sooner we realise this and demystify the inner-workings of AI, we can instead focus on how such programmes can be used and developed intelligently and responsibly.

Reflecting on the development process of AI is also important to consider. The development of generative AI tools, such as ChatGPT and DALL-E, require vast amounts of training data, computing power and highly-skilled researchers. Unfortunately, only a select few large technology companies like Google, Microsoft, and Amazon have the resources to fund these models. As a result, academics and independent researchers are often placed at a disadvantage, unable to compete due to the lack of resources and funding.

This monopolisation of AI technology by large private companies is referred to by AI experts as “industrial capture”. [5] Researchers from MIT have called on policy makers to be wary of the phenomenon, as they see more and more deep-learning research shifting from academia to private industry.

While this shift may benefit consumers, it could limit alternatives for critical AI tools that focus on public interest. Left unchecked, industrial capture will lead to the concentration of power and influence in the hands of a few large corporations, potentially exacerbating the ethical and social concerns surrounding the use of AI and its development. [6]

To achieve this fairer future would require a shift from the capitalist race for market share and profit, towards a model that balances technological advancement with public interests. The race for commercial AI dominance is already underfoot, and with this comes the need for a new sense of urgency and responsibility.

But it proves a real challenge to work towards designing responsible AI. It involves ensuring that AI systems do not perpetuate bias, discrimination, or harm, and that they are aligned with public interest.

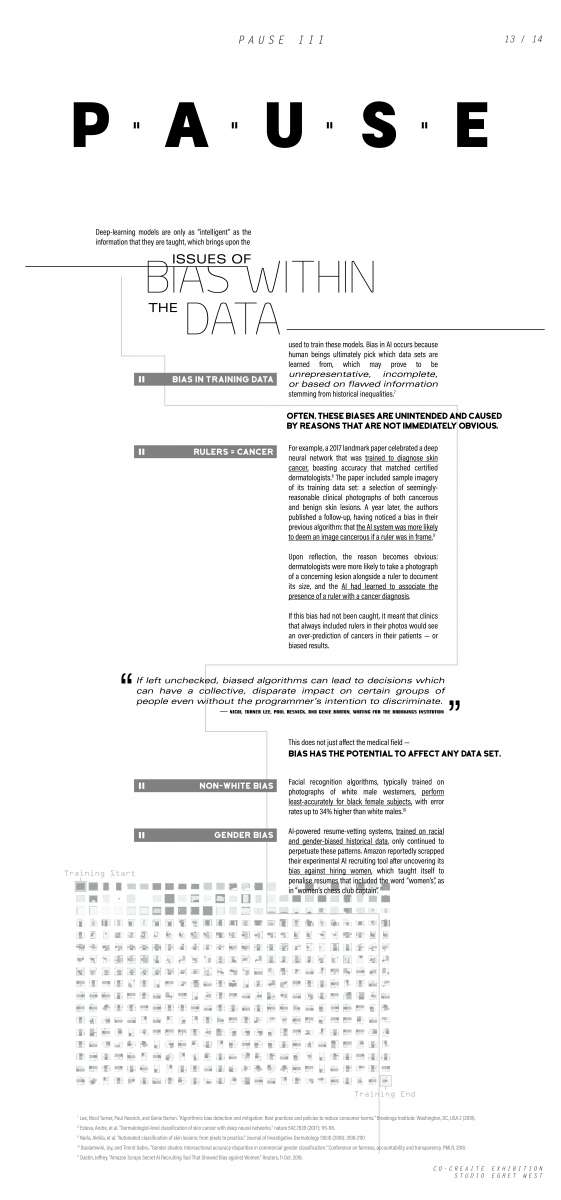

Deep-learning models are only as “intelligent” as the information that they are taught, which brings upon the issues of bias within the data used to train these models. Bias in AI occurs because human beings ultimately pick which data sets are learned from, which may prove to be unrepresentative, incomplete, or based on flawed information stemming from historical inequalities. [7]

Often, these biases are unintended and caused by reasons that are not immediately obvious.

For example, a 2017 landmark paper celebrated a deep neural network that was trained to diagnose skin cancer, boasting accuracy that matched certified dermatologists. [8] The paper included sample imagery of its training data set: a selection of seemingly-reasonable clinical photographs of both cancerous and benign skin lesions. A year later, the authors published a follow-up, having noticed a bias in their previous algorithm: that the AI system was more likely to deem an image cancerous if a ruler was in frame. [9] Upon reflection, the reason becomes obvious: dermatologists were more likely to take a photograph of a concerning lesion alongside a ruler to document its size, and the AI had learned to associate the presence of a ruler with a cancer diagnosis. If this bias had not been caught, it meant that clinics that always included rulers in their photos would see an over-prediction of cancers in their patients — or biased results.

If left unchecked, biased algorithms can lead to decisions which can have a collective, disparate impact on certain groups of people even without the programmer’s intention to discriminate.”Nicol Turner Lee, Paul Resnick, and Genie Barton, writing for the Brookings Institution

This does not just affect the medical field — bias has the potential to affect any data set. Facial recognition algorithms, typically trained on photographs of white male westerners, perform least-accurately for black female subjects, with error rates up to 34% higher than white males. [10] AI-powered resume-vetting systems, trained on racial and gender-biased historical data, only continued to perpetuate these patterns. Amazon reportedly scrapped their experimental AI recruiting tool after uncovering its bias against hiring women, which taught itself to penalise resumes that included the word “women’s”, as in “women’s chess club captain”. [11]

"Simple Steps Towards A Happier Space" by Freddie Hong

This door requires you to express happiness through your smile in order for it to open.

In today’s world, facial recognition technology is becoming increasingly pervasive, allowing our built environment to not only recognise our presence, but also identify our emotional state and other personal attributes such as gender, age and ethnicity.

Doors, symbolic features of building control, typically have two binary states: “open” or “closed”. Similarly, this particular door classifies the visitor’s emotional state, specifically whether they are “happy” or “not happy”, before allowing them entry.

This artwork creates a scenario whereby emotions are dictated and judged by a non-human entity. Each visitor’s smile is evaluated and given a score based on its conformity to a training dataset, and the door only opens upon achieving the minimum score. This aspect of the artwork critiques dataset biases within machine learning, whereby unrepresentative or poor datasets often leads to discriminatory results.

The inspiration for this project stemmed from the artist’s personal experience at an automated photo-taking booth at a UK visa application centre, where his picture was rejected multiple times due to its “non-conformity”.

Privacy is another important issue which surrounds AI. These systems yearn for bigger and better training data sets, but where is this data coming from? Take the example of Alibaba’s City Brain (see “Performative”), where automatic systems capture data from mapping phone apps, public transportation networks and CCTV cameras — most of these are so ubiquitous and ingrained into daily life, making avoiding them impossible — bringing up questions over privacy and surveillance. Concerningly, Xian-Sheng Hua, who manages AI at Alibaba, said at the 2017 World Summit AI that “in China, people have less concern with privacy, which allows us to move faster”. [12]

Dr Gemma Galdon-Clavell, a leading voice on technology ethics and algorithmic accountability, agrees that the implications of such data-grabs are huge. Galdon-Clavell explains that these systems need oversight and control, not only of stated intended uses, but also future ones. [13]

“What is sold as a public or safety initiative ends up using public infrastructure and the public to mine data for private uses”, she says. She also argues that projects such as these have the potential for massive data breaches, and that data security should also be made a top priority, especially with the increasing dependence on centralised systems that can be hacked. Privacy should be safeguarded by data governance, to protect and allow individuals to manage their personal data. This will also help to develop trust and incentivise the uptake of data sharing models, ultimately improving AI systems.

As AI grows more pervasive, policymakers have new responsibilities to ensure that the technology is safely developed. Paving the way, the European Union (EU) first proposed the Artificial Intelligence Act in 2021, with a “general approach” position adopted in 2022, and the legislation currently under discussion by the European Parliament. [14]

With this Act, the EU is taking the lead in attempting to make AI systems fit for the future we as humans want.”Kay Firth-Butterfield Head of AI at the World Economic Forum

The focus of the Artificial Intelligence Act is to enhance regulations regarding data quality, transparency, accountability, and human oversight. It also aims to address ethical dilemmas and implementation obstacles in different industries, including finance, healthcare, energy, and education. This Act would be one of the most comprehensive regulatory frameworks for AI in the world, and could set a precedent for other countries and regions to follow.

Other dedicated individuals and organisations are working hard to raise awareness of the need for change. Institutions like the AI Now Institute, the Center for Humane Technology, and the Institute for Ethical AI & Machine Learning are just a few examples of organisations that are dedicated to improving the ethics and accountability of AI. Collectively, their work includes addressing the issues of power concentration within the tech industry, steering technology towards prioritising human well-being, and ensuring that AI is developed in a responsible and ethical manner.

In the end, the key to developing truly transformative AI lies not just in technological innovation, but in our ability to collectively navigate the complex social, economic, and ethical challenges that arise along the way. By working together to build a more equitable and inclusive future, we can ensure that the benefits of AI are shared by all, and that we are able to harness its full potential for the greater good.

If our dystopia is bad enough, it won't matter how good the utopia we want to create. We only get one shot, and we need to move at the speed of getting it right.”The AI Dilemma Center for Humane Technology

References

- Beall, Abigail. “In China, Alibaba’s Data-Hungry AI Is Controlling (and Watching) Cities.” Wired UK, www.wired.co.uk/article/alibaba-city-brain-artificial-intelligence-china-kuala-lumpur. Accessed 18 May 2023.

- City of Copenhagen. “‘Connecting Copenhagen’ Is the World’s Best Smart City Project.” State of Green, 10 Dec. 2014, stateofgreen.com/en/news/connecting-copenhagen-is-the-worlds-best-smart-city-project/.

- Zach Stein-Perlman, Benjamin Weinstein-Raun, Katja Grace, “2022 Expert Survey on Progress in AI.” AI Impacts, 3 Aug. 2022. https://aiimpacts.org/2022-expert-survey-on-progress-in-ai/.

- Lanier, Jaron, “There Is No A.I.” The New Yorker, 20 Apr. 2023, www.newyorker.com/science/annals-of-artificial-intelligence/there-is-no-ai.

- Nur Ahmed et al. The growing influence of industry in AI research. Science 379, 884-886 (2023).

- Murgia, Madhumita, “Risk of “Industrial Capture” Looms Over AI Revolution.” Financial Times, 23 Mar. 2023, www.ft.com/content/e9ebfb8d-428d-4802-8b27-a69314c421ce.

- Lee, Nicol Turner, Paul Resnick, and Genie Barton. "Algorithmic bias detection and mitigation: Best practices and policies to reduce consumer harms." Brookings Institute: Washington, DC, USA 2 (2019).

- Esteva, Andre, et al. "Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks." nature 542.7639 (2017): 115-118.

- Narla, Akhila, et al. "Automated classification of skin lesions: from pixels to practice." Journal of Investigative Dermatology 138.10 (2018): 2108-2110

- Buolamwini, Joy, and Timnit Gebru. "Gender shades: Intersectional accuracy disparities in commercial gender classification." Conference on fairness, accountability and transparency. PMLR, 2018.

- Dastin, Jeffrey. “Amazon Scraps Secret AI Recruiting Tool That Showed Bias against Women.” Reuters, 11 Oct. 2018,

- Revell, Timothy . “A Smart City in China Tracks Every Citizen and Yours Could Too.” New Scientist, www.newscientist.com/article/2151297-a-smart-city-in-china-tracks-every-citizen-and-yours-could-too/. Accessed 18 May 2023.

- Beall, Abigail. “In China, Alibaba’s Data-Hungry AI Is Controlling (and Watching) Cities.” Wired UK, www.wired.co.uk/article/alibaba-city-brain-artificial-intelligence-china-kuala-lumpur. Accessed 18 May 2023.

- Feingold, Spencer. “The EU’s Artificial Intelligence Act, Explained.” World Economic Forum, 28 Mar. 2023, www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/03/the-european-union-s-ai-act-explained. Accessed 18 May 2023.

Deimante Bazyte

Managing a team that spans 3D, motion, and mixed reality, I focus on bringing clarity to complex ideas.”

Isabella West

I enjoy getting people together from different disciplines - from our clients and collaborators as well as local communities.”

Dominic Ramli-Davies

It is vital to instil a sense of playfulness and enjoyment through one’s design approach.”

Jarrell Goh

Architectural designer, illustrator, digital visualiser, drone pilot, photographer, or filmmaker - every day brings a new surprise!”